The Answer to How Is Yes

The Answer to How Is Yes

by Peter Block

Peter Block is a “secular” writer who advises corporations, organizations, NPOs, and individuals on how to better achieve their goals. As I read the book, I realized that I have never come across a better book on the nature of faith. This book affirms some of my most deeply held beliefs and has given me some great tools for pursuing what truly matters in life. It should be put into the hands of as many people as possible, from the high school graduate to the long-time leader. Below is my attempt at a summary for those of you who will never take the time to read the whole text. Hopefully it will whet your appetite for more. I make some comments of my own, but mostly it is a compilation of quotes from the author, which are footnoted.

Block begins his book by tackling the nature of “how” questions, showing that often they are cover-ups for doubt and resistance to going forward with new and creative ideas.

Block shows that how questions often issue from a dependence upon the engineer and economist mindsets that evaluate all issues in terms of utility and cost. Will it work and will it produce a profit? They presuppose that someone out there knows how to do it right, and it is not us! Here are some examples of how questions.

- How do you do it?

- How much will it cost?

- How long will it take?

- How do we know this will work?

Block insists that these types of questions may be genuine requests for more understanding, but often they are roadblocks created by doubt and resistance to change. He recommends replacing “how” questions with what he calls “yes” questions, which will be illustrated later.

If something is worth doing, it is because it has intrinsic value, not simply because it is easily accomplished or will render a profit.

Once we decide that something needs to be pursued and make the commitment to do it, then we can more properly address the how questions. Necessity is the mother of invention.

Acting on what matters is, ultimately, a political stance by which we declare we are accountable for the world around us and are willing to pursue what we define as important, independent of whether it is in demand or has market value. 1

From the point of view of being a follower of Christ who is committed to disciple making, this is a crucial statement. We tend to evaluate programs and goals by whether they work from a programmatic and financial point of view, rather than whether Jesus commanded it. As individuals we also easily fall into this trap and end up leading lives of “quiet desperation,” as Thoreau put it, because we never pursue what matters most to us. Instead we succumb to the rat race and the siren song of “making a living.”

Our culture is not organized to support idealistic, intimate, and deeper desires. It is organized to reinforce instrumental behavior. If we can understand the nature of the culture, we gain some choice over it. 2

The How Questions

How do you do it?

This question seems innocent enough, but it carries a lot of hidden baggage.

The question carries the belief that what I want is right around the corner, and all that prevents me from turning that corner is that I lack information or some methodology. What this question ignores is that most of the important questions we face are paradoxical in nature. A paradox is a question that has many right answers, and many of the answers seem to conflict with each other. 3

In other words, how questions can lead us to postpone doing anything until we feel we understand how to do it and eliminate the possibility of failure. Faith, on the other hand, requires us to pursue the right thing without always knowing how to do it or how things will turn out, trusting that the way forward will be made known as we go.

How long will it take?

The most important effect of the “How long?” question is that it drives us toward answers that meet the criteria of speed. It runs the risk of excluding slower, more powerful strategies that are more in line with what we know about learning and development. We treat urgency like a performance-enhancing drug, as if calling for speed will hasten change, despite the evidence that authentic transformation requires more time than we ever imagined. 4

From a discipleship perspective, helping people become committed followers of Christ takes far longer than any programmatic approach would be willing to endure. If we demand quick results, we may miss out on the deeper work of the Holy Spirit in people’s lives and short circuit God’s plan. If we are going to be “organic” and led by God’s Spirit, we must let people grow as the Lord enables them. People mature at various rates, and we cannot program change at the deepest level. We must be committed to the long haul, not to the instant gratification and results that the world craves.

How much does it cost?

The question of cost is first cousin to the question of time. Instead of instant gratification, we seek cheap grace. The question makes the statement that if the price is too high, this will be a problem. It embodies the belief that we can meet our objectives, have the life and institutions that we want, and get them all at a discount. It carries the message that we always want to do it for less, no matter how rich we are. 5

In the church world, far too often we constrict ourselves by using models that “work” financially, but which do not allow us the freedom to carry out the Great Commission by making authentic disciples who in turn make disciples. The deception is that we must keep the “sheep” happy if we are to have enough money to do the work of ministry. Fearing the loss of income, many church leaders cave to the desires and demands of immature church members to be “fed” and entertained, instead of focusing on providing them with what they truly need – discipleship.

True freedom comes when we believe that the Lord will provide when we step out in faith to pursue what is highest on his priority list, the making of disciples.

The world mocks the caricature of Christianity that overtly pursues money instead of God’s kingdom. Faith allows us to pursue a different model, regardless of the cost, since God has is our Provider. Isn’t it time for the church to silence its critics by living out our faith by pursuing what matters most regardless of the cost or consequences?

Regardless of our personal stance on an issue, when we zero in on cost too soon we constrain our capacity to act on certain values. We value people, land, safety, and it is never efficient or inexpensive to act on our values. There is no such thing as cheap grace. When we consider cost too early or make it the overriding concern, we dictate how our values will be acted upon because the high-cost choices are eliminated before we start. 6

How do you get those people to change?

This is what Block calls the power question. It concerns itself with controlling others to get the outcome we desire, and it betrays that we think our ability to act on what truly matters hinges on what others do.

…our focus on “those people” is a defense against our own responsibility. The question “How do you get those people to change?” distracts us from choosing who we want to become and exercising accountability for creating our environment. 7

…we surrender our freedom and our capacity to construct the world we inhabit when we focus on their change. No one is going to change as a result of our desires. In fact, they will resist our efforts to change them simply due to the coercive aspect of the interaction. People resist coercion much more strenuously than they resist change. Each of us has a free will at our core, so like it or not, others will choose to change more readily from the example set by our own transformation than by any demand we make of them (emphasis mine).” 8

How Do We Measure It?

Measurement is one of the main components of the legalistic mindset and the engineering archetype. Grace asks us to accept that we have a great relationship with God based on a gift and a promise. Legalism wants to impose some external way to gauge or measure how we are doing and how we measure up against God’s or our own standard of righteousness. Block addresses this from a personal and organizational point of view.

We justly want to know how to measure the world. We want to know how we are doing. We need to know where we stand. But the question of measurement ceases to serve us when we think that measurement is so essential to being that we only undertake ventures that can be measured. Many of the things that matter the most defy measurement. 10

Our obsession with measurement is really an expression of our doubt. It is most urgent when we have lost faith in something. Doubt is fine, but no amount of measurement will assuage it. Doubt, or lack of faith, as in religion, is not easily reconciled, even by miracles, let alone by gathering measurable evidence on outcomes. 11

Measurement is also tricky because we think that the act of measurement itself is a motivational device, and that people will not act on what is not institutionally valued through measurement. This shrinks human motivation into a cause-and-effect dynamic. It implies that if we do not have a satisfactory answer to the measurement question, then nothing will get done. 12

How Have Other People Done It Successfully?

“Where else has this worked?” is a reasonable question, within limits. It is dangerous when it becomes an unspoken statement: If this has not worked well elsewhere, perhaps we should not do it. The wish to attempt only what has been proven creates a life of imitation. We may declare we want to be leaders, but we want to be leaders without taking the risk of invention. The question “Where else is this working?” leads us down a spiraling trap: If what is being recommended or contemplated is, in fact, working elsewhere, then the next question is whether someone else’s experience is relevant to our situation— which, upon closer scrutiny, it is not. The value of another’s experience is to give us hope, not to tell us how or whether to proceed. 13

“Yes” Is the Right Question

The right questions are about values, purpose, aesthetics, human connection, and deeper philosophical inquiry. To experience the fullness of working and living, we need to be willing to address questions that we know have no answer. When we ask How? we limit ourselves to questions for which there is likely to be an answer, and this has major implications for all that we care about. The goal is to balance a life that works with a life that counts. The challenge is to acknowledge that just because something works, it doesn’t mean that it matters . 14

Yes is the answer— if not the antithesis— to How? Yes expresses our willingness to claim our freedom and use it to discover the real meaning of commitment, which is to say Yes to causes that make no clear offer of a return, to say Yes when we do not have the mastery, or the methodology, to know how to get where we want to go. Yes affirms the value of participation, of being a player instead of a spectator to our own experience. Yes affirms the existence of a destination beyond material gain, for organizations as well as individuals. 15

Is not this the very soul of faith? Walking with God is a journey into the unknown which is made palatable because the utterly trustworthy God walks with us!

Yes questions contrast starkly how questions. Here are some examples.

What refusal have I been postponing?

If we cannot say no, then our yes means nothing. 16

This is not an argument against following the direction provided by others. It is simply a litmus test: Have we freely chosen to follow their direction, or do we do so out of compliance and a fear of refusing? While we may be doing the same thing either way, the context of our action is everything. 17

What commitment am I willing to make?

The question of commitment declares that the essential investment needed is personal commitment, not money, not the agreement of others, not the alignment of converging forces supportive of a favorable outcome.

For anything that matters, the timing is never quite right, the resources are always a little short, and the people who affect the outcome are always ambivalent. These conditions offer proof that if we say yes, it was our own doing and it was important to us. What a gift. 18

What is the price I am willing to pay?

When we say Yes instead, we acknowledge that acting on what we choose costs us something, which is what gives it value. If there were no price to saying Yes, to acting in the face of our doubts and meager methodology, then the choice we make would have no meaning. 19

What is my contribution to the problem with which I am concerned?

This question also shifts the nature of accountability. It is the alternative to being “held” accountable, because it asks us to choose accountability… What keeps us stuck is the belief that someone or something else needs to change before we can move forward… We affirm that we are not a spectator, but a player, and in the end we have no one to blame but ourselves. 20

What is the crossroad at which I find myself at this point in my life/ work?

This question affirms the idea that it is the challenge and complexity of life and work that gives it meaning. We expected to live happily ever after and find that yesterday’s triumph is no longer enough. There is no level of success from which we can wade into shore. This question is especially important if what we have done in the past has been successful, for what worked yesterday becomes the gilded cage of today. It is the answer to this question that gives us clues to what matters most. The fact that we acknowledge we are at a crossroad gives us the energy to get through the intersection. We will find meaning in exploring and understanding this crossroad. Our crossroad represents an as yet unfulfilled desire to change our focus, our purpose, what we want to pursue. 21

What do we want to create together?

This question recognizes that we live in an interdependent world, that we create nothing alone. We may think we invented something, or achieved something on our own, but this belief blinds us to all that came before and those who have supported us . It is a radical question, for it stabs at the heart of individualism, a cornerstone of our culture. It also declares that we will have to create or customize whatever we learn or whatever we import from others. We may think we can install here what worked there, but in living systems, this is never the case. 22

How to Change from How to Yes Questions

How do you do it? becomes What refusal have I been postponing?

“Granted, refusal is a strange way of saying yes. But when our plate is full and we seek a change, knowing what we need to say no to is essential to invention.” 23

How long will it take? becomes What commitment am I willing to make?

“We have time for all that is truly important to us, so the question of time shifts to What is important? When we say something takes too long, it just means that it does not matter to us.” 24

How much does it cost? becomes What is the price I am willing to pay?

“The ultimate price is the willingness to fail and get hurt if it does not work . This is the more important discussion and leads to a more realistic consideration of whether or not the price is too high.” 25

How do you get those people to change? becomes What is my contribution to the problem I am concerned with?

“The Yes question embodies Gandhi’s idea that we need to become the change we want to see. This keeps us honest. It is the antidote to our need to control others.” 26

How do we measure it? becomes What is the crossroad at which I find myself at this point in my life/ work?

The central question in exploring a change is whether or not what we are considering will have meaning for us, for the institution, for the world. Concrete measures can determine progress, but they do not really measure values. The crossroad question helps to define what has personal meaning for us, which is the first-order question. We pursue what matters independently of how well we can measure it… 27

How are other people doing it successfully? becomes What do we want to create together?

These questions represent the tension between what is proven and what is still to be discovered… What will matter most to us, upon deeper reflection, is the quality of experience we create in the world, not the quantity of results… Following a recipe assumes there is a known path to finding our freedom and that someone else knows it. Freedom asks us to invent our own steps. The phrase that expresses this most clearly is “to be the author of our own experience.” 28

Defenses Against Acting

The most difficult aspect of acting on what matters is to come face to face with our own humanity— our caution, our capacity to rationalize, our willingness to fit into the culture rather than live on its margin. This is true in our neighborhood, among colleagues, and in the workplace. Fundamentally, to act fully on what matters means we are asked to claim our freedom and live with the consequences… As long as we wish for safety, we will have difficulty pursuing what matters…Knowing how to do something may give us confidence, but it does not give us our freedom. Freedom comes from commitment, not accomplishment… To live our lives fully, to work wholeheartedly, to refuse directly what we cannot swallow, to accept the mystery in all matters of meaning—this is the ultimate adventure. The pursuit of certainty and predictability is our caution speaking.Freedom is the prize, safety is the price, what is required is faith more than fact and will more than skill. 29

Recapturing the Idealism of Youth

Webster’s definition of an idealist is “one who follows their ideals, even to the point of impracticality.” This takes us right to the place we want to be, the place of practicality in the pursuit of our desires. It confronts us with the question of who decides what is possible and what is practical. Who draws the line, and do we perhaps yield too quickly on what others define as impractical?… Early in the game the child is asked to shift from experiencing life to preparing for it. The push towards early adulthood undermines the possibility of prolonged idealism… Real commitment is a choice I make regardless of what is offered in return… Idealism is the willingness to pursue our desires past the point of practicality. The surrender of desire is a loss of part of our self. 30

Enduring the Depth of Philosophy

If acting on what matters needs idealism and intimate contact, it also calls us to go deeper into ourselves and become more reflective towards what we most care about. This includes giving ourselves time and space to think independently and to value the inward journey. Without the willingness to go deeper, there is little chance for any authentic change… The things that matter to us are measured by depth… Instead of doing what matters, I spend my life doing what works. It increases my market value and postpones the question of my human value… If we decide to act on what matters, then we shift our consciousness about pace. There is always time to do everything that really matters: If we do not have time to do something, it is a sign that it does not matter… There is simply no way to shorten the time that depth requires. Any of the values we hold dear wilt under the pressure of time. It is difficult to imagine instant compassion, instant reconciliation, or instant justice. If we yield to the temptation of speed, we short-circuit our values. 31

The Requirements

Obtaining Full Citizenship

Maybe the unvarnished meaning of growing up is the acceptance that living out our values, and also winning the approval of those who have power over us, is an unfulfillable longing. When we grow up emotionally, or claim our citizenship politically and organizationally , we lose the protection of the parental world. Acting on what matters means that we will consistently find ourselves feeling like we are living on the margin of our institutions and our culture. This calls for some detachment from the mainstream… We decide to move far enough to the edge of the culture to see it clearly. What is the norm and normal does not serve us well. Many of us have tried hard to live a “normal” life, and how is it going?… This means we have to be willing to be abnormal and imperfect. We have to be willing to see clearly and to question what others seem to condone. Any answer given by the dominant culture will never suffice…We recognize the difference between being a citizen and being a consumer. The difference between subject and object. Citizens have the capacity to create for themselves whatever they require. Citizens have power, customers have needs… Needs give rise to products that create the illusion that they can give us what we desire. Consumers surrender their freedom for the sake of convenience , safety, personal gain, superiority, pleasure, material value. Pretty appealing, but not worth the price. So we act as citizens, being accountable for reconstituting the world around us. This means we stop complaining. Complaining is the voice of our helplessness… We choose activism. We dive into the world and swim beneath the surface. We become activists, moving out of electronic enclosures into the neighborhood, into the community, acting to raise the consciousness of everyone we contact. We are a convening agent of human beings in human settings. Wherever people gather, first and foremost, we connect them with each other. We are peers joining together to change the world, not individuals negotiating with our leaders… The actions that matter to us most are the ones we will remember. What is critical is to choose activism and depth as our strategy… We expect our values to be embodied in all that we do. 32

The Boss

But when all is said and done, your boss is not your best source of feedback. It is not that bosses don’t wish to be helpful. They do. But they aren’t. Of course, all bosses pride themselves on how they help develop people, but this does not make them good at it. Remember that all patriarchs believe in participation, they just feel their particular people aren’t quite ready for it. You may have had a boss that did in fact help greatly in your development, but to keep looking for this is a defense against getting on with it yourself, regardless. Also, much of our suffering comes from having internalized the opinions of others. This was the reality of being a child, when our parents’ definition of us was understandably powerful. But to continue this process as an adult is not smart… As an individual free to create the world we live in, I carry the cause for how my boss and others respond to and treat me. Once I understand this and stop trying to control them, I can get on with the business of acting on what matters. Others, our bosses included, are more likely to reflect on their own behavior as a result of witnessing our self-reflection than yield to our desire for them to be different… Carl Jung said that disobedience is the first step towards consciousness. Not only are we not here to fear or please our bosses, but we should realize there is meaning and value in our acts of disobedience— not disobedience for its own sake, but as a fuller expression of our own unique humanity and purpose. The fact that we are disappointing authority may be a sign that we have begun to live our own lives, that we have become fully engaged. We do not know that our lives are our own until we have paid for the choices we make. This is choosing adventure over safety. The adventure we can trust is the journey towards our own freedom and our belief in what is real and valuable. 33

We must be careful to distinguish between disobedience to the external forces which try to shape our lives against God’s higher purpose for us and outright rebellion against authority for sinful reasons. The first may be an act of obedience to God, but the latter never is.

We all live with people who have power over us and we need to come to terms with them. We affirm our own freedom and our commitment to an institution when we look past the behavior of a boss and respond to their intent. We always have the choice to offer the benefit of the doubt, earned or not. We can decide that management has the best interests of the institution at heart and we can work to understand their intentions, even if their tactics do not seem to be aligned with their purpose. 34

Ambition

The promise of full membership and its security is what we have to give up for our genuine freedom, our ultimate security, and a life that matters. Growing up and claiming our citizenship is accompanied by the realization that it is our ambition that leads us into the arms of the culture. I am speaking here of our ambition to rise to a position of institutional power, to be recognized by our profession, to be offered the keys to a gated community… It is important to recognize that giving up ambition does not mean we are giving up desire, just the opposite. Ambition , again, means seeking recognition from our institutions, their leaders, and our profession. We trade ambition for choices about what matters, about how we choose to operate, and about what we choose to create. What is affirmed is our determination to do good work, with or without approval. When we choose this idealism, we negate the mindset that it is human nature to pursue self-interest, that people do mostly what they are rewarded for, and that if something does not get measured, it does not get done. Giving up our ambition doesn’t mean we have to change jobs or go anywhere. We just have to get the point. We postpone the How? questions. We say Yes and get on with it. Giving up our ambition is not easy. Acting on our values and achieving recognition from the world are both real and universal longings, and both matter. The problem is we must begin with caring about the world, which means acting on our values. The idea is first to embrace the task of reconstituting the world and then hope you get some support for it. It is the reconstruction, or transformation, of the culture by our living example, our words, and our commitments that is our fundamental work. 35

“I am responsible for the health of the institution and the community even though I do not control it. I can participate in creating something I do not control.” 36

The essence of Christianity from an organizational point of view revolves around letting go of the groups God may use us to form through evangelism and discipleship. Just as good parents let go of their children as part of the process of helping them attain responsible adulthood, church leaders must train and release their disciples so that they can become self-governing leaders in their own right. This militates against the Babelish desire for ambitious centralization and control that has plagued mankind for millennia.

Instrumentality

Instrumentalism is a philosophic stance. It is “a pragmatic doctrine that ideas are plans for action serving as instruments for adjustment to the environment and that their validity is tested by their effectiveness” (Webster again). To act on what is instrumental requires us to view the world according to how effective it is, how much leverage it can provide us, what return we receive on our investment. 37

Here we have in a nutshell what is most dangerous to the church. Churches are not “for profit” enterprises. They are “for people” and “for God’s kingdom,” which is entirely different. We must accept Jesus’ clear teaching that it is impossible to serve both God and Mammon.

Archetypes

The Engineer

Change management to an engineer-turned-manager is about clear goals , consistent practices, predictable results, and accurate measurements. This demands a clear objective, a concrete definition of the process, and a reliable tracking system. It matters less what the plan is, whether it has any larger meaning or, in the extreme, is even worth doing. They just need a plan and need to know how they are going to measure what they do. A core management-as-engineer belief is that if you cannot measure something, either it should not be undertaken or it does not exist… Here are some highlights of the engineering archetype for achieving change and acting on what matters:

- Leadership articulates a clear objective.

- Define roles and responsibilities clearly.

- Prescribe the behavior that you want.

- Assess often and give good feedback.

- Control the emotional side of work.

- Think of employees as one more asset.

The engineering viewpoint transforms human beings into human assets and human resources… This is a characterization of the engineer as cultural archetype, not the individual engineer you may know. It is the engineer archetype that has guided our passion for what works. When we want to change or improve our world, it leads us into strategies of control and installation and is indifferent to any discussion of subjective experience. We have embraced the engineering genius and brought it into all aspects of our lives, especially our institutions.

Thus, the engineering mind is key to our materialism. It does not create it, but reinforces it through valuing all that is practical and useful, and this is exactly what matters to an engineer. 38

The Economist

The economist takes what the engineer provides and attaches a monetary value to it.

The essence of the economist stance on people is that the exchange of tangible value explains human motivation and defines organizational purpose. It is the belief that barter is the means by which we get things done, deliver service, and even find love. At the simplest level, the economist believes that we are all for sale or rent, for this is the dynamic of exchangeable self-interest… The economist believes that money, tangible rewards, or other incentives is what causes us to do what we do. My willingness to change my behavior, to support an institution, or to engage in a relationship is, fundamentally, a negotiation between what I am asked to give and what I think I can get… What is of interest is that our culture has generally adopted the economist view of human motivation. We use an economic model to explain why people do what they do. We define for-profit organizations as primarily economic entities, and anything that does not clearly offer a return on an investment undergoes close scrutiny. We also view relationships in terms of transaction and exchange. Pure acts of charity and goodwill are viewed with skepticism,… The economist view of acting on what matters or initiating change centers on incentives:

- Refocus the reward system.

- Competition is essential to success.

- Barter is a major basis for motivation and action.

- Apply a cost-benefit analysis to every action.

- Grow or die.

Management, according to the economist archetype, becomes an exercise in budget control, and this is the basis of power… When cost and time become the very first questions, instead of just important ones, they create a culture of constraint, one in which the future is much like the past, only more efficient. Instead of creating a future, the economist, along with the engineer, focuses on predicting and controlling it… The impact of the economist-as-manager is that relationships between organizations and their members become increasingly commercialized… The economist mentality is not so much wrong , as it is narrow. It is this limited view of what is possible that brings into question the potential of calling, commitment, care, passion , and all the values that grow out of idealism, intimacy, and depth. 39

The Artist

Basically the artist is the opposite of the Engineer / Economist. This archetype views the other two with great suspicion.

Thus, the strategy for the artist to act on what matters rests on the belief that if something can be clearly pictured, vividly described and shown to a waiting world, enough has been done. Transformation in an artist’s mind comes from understanding and interpreting the emotional landscape, not avoiding it. Installation, a keyword to the engineer, means to the artist the process of hanging paintings in a gallery. The artist as social scientist believes that awareness leads to change,… 40

The artist has a hard time in a management role because he or she is ambivalent toward authority and has a hard time using it.

The Architect

The author believes the architect is the archetype that can bring together the economist, the engineer, and the artist. The architect seeks to construct something which will be sound from an engineering perspective and within budget, but is also fulfilling from an artistic and human point of view. Block advocates for what he calls social architects, minus the negative political baggage.

We might even say that the role of the social architect is to create service-oriented organizations, businesses, governments, and schools that meet their institutional objectives in a way that gives those involved the space to act on what matters to them. The social architect is one answer to what replaces command and control. It is a role for bosses and employees, it is not a technical specialty. Focusing on the boss for a moment, the boss has a responsibility to fulfill the promises of the organization to its stakeholders— shareholders, board members, community, customers, and citizens. It is the rightful duty of the boss to speak for those who commission and are served by the institution. The boss also has the obligation to provide navigational insight as to how the institution keeps its promises, and this is where the social architect is required. It is the task of the social architect to bring about needed change while using methods that are based on the deeply held personal values of the members… The fact that we are living in an engineer-economist dominated world creates a bias toward more control than freedom, more practicality than idealism, barter rather than intimacy, and greater speed more than depth. The choice to think of ourselves as social architects is an activist stance— radical in thinking, conservative and caring in action…To be a citizen is to show up— to accept the invitation to participate, or to create it if it is not offered, to act as a co-designer. At any moment we can choose to speak of our idealism, express our feelings, and reflect on and deepen our questions. Acting on what matters is an act of leadership, it is not dependent on the leadership of others. Thus, all of the capacities of the social architect described below are open to each of us… Implied in all of this is the idea that engagement is the design tool of choice; it is how social and cultural change happens. For complex challenges, especially when we create a system that goes against the default culture, dialogue itself is part of the solution. We need to believe that conversation is an action step. It is not only a means to the end, it is also an end in itself…41

Block points out that the social architect as leader’s job is to convene people in order to ask the proper questions that will stimulate dialog and buy in from the rank and file. To understand more about this process, I highly recommend another of Block’s books entitled, Community: The Structure of Belonging.

Conclusion

It is apparent to me that for far too long (since the age of Constantine?) the church has allowed the engineer and economist archetypes to rule at the expense of following the Holy Spirit (God’s architect) and operating by faith.

This has become more the case due to the growing belief that churches, especially the largest ones, are best run as businesses. The traditional pastor has been replaced, in some cases, by a CEO who views things rather much like any other CEO in terms of production, operations, effectiveness, instrumentality, and costs. Until we give up our addiction to Mammon, the church will lack the adventurousness (faith) that characterized it during the first century. Block’s book will open your eyes to the roots of the problem, but we each must navigate how to apply these truths to our own situation. Long live the architect, which by the way is the transliteration of the Greek word archetekton, translated “master builder” or apostle in 1 Corinthians 3:10!

Footnotes

1 Block, Peter (2003-11-01). The Answer to How Is Yes: Acting on What Matters (Kindle Locations 140-142). Berrett-Koehler Publishers. Kindle Edition.

2 Ibid. Kindle Locations 215-216

3 Ibid., Kindle Locations 240-243

4 Ibid., Kindle Locations 271-274

5 Ibid., Kindle Locations 275-278

6 Ibid. Kindle Locations 286-289

7 Ibid., Kindle Locations 313-316

8 Ibid., Kindle Locations 316-321

10 Ibid., Kindle Locations 327-329

11 Ibid., Kindle Locations 335-337

12 Ibid., Kindle Locations 342-345

13 Ibid., Kindle Locations 347-352

14 Ibid., Kindle Locations 366-370

15 Ibid., Kindle Locations 370-374

16 Ibid., Kindle Locations 378-380

17 Ibid., Kindle Locations 389-390

18 Ibid., Kindle Locations 396-399

19 Ibid., Kindle Locations 406-408

20 Ibid., Kindle Locations 416-421

21 Ibid., Kindle Locations 422-428

22 Ibid., Kindle Locations 430-434

23 Ibid., Kindle Locations 456-457

24 Ibid., Kindle Locations 463-464

25 Ibid., Kindle Locations 475-476

26 Ibid., Kindle Locations 480-481

27 Ibid., Kindle Locations 485-488

28 Ibid., Kindle Locations 492-493, 502-503, and 511-513

29 Ibid., Kindle Locations 527-529, 598, 601-602, and 624-626

30 Ibid., Kindle Locations 659-661, 671-672, 687-688, and 701-702

31 Ibid., Kindle Locations 904-906, 962-964, and 969-975

32 Ibid., Kindle Location 1004-1007, 1049-1050, 1052-1059, 1070-1073, 1077, and 1079

33 Ibid., Kindle Locations 1311-1316 and 1355-1367

34 Ibid., Kindle Locations 1389-1393

35 Ibid., Kindle Locations 1435-1438 and 1456-1465

36 Ibid., Kindle Locations 1597-1598

37 Ibid., Kindle Locations 1619-1624 and 1682-1684

38 Ibid., Kindle Locations 1776-1797 and 1804-1809

39 Ibid., Kindle Locations 1819-1824, 1828-1831, 1833-1835, 1838-1852, 1855-1856, 1863-1865, 1868-1870, 1875, and 1881-1883

40 Ibid., Kindle Locations 1913-1916

41 Ibid., Kindle Locations 2019-2026, 2032-2034, 2036-2039, 2110-2113, and 2137-2140

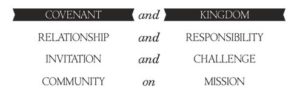

As members of the covenant family we are in relationship with God and one another. We have a responsibility to invite others through the Gospel to enjoy the same covenant privileges as we enjoy. This is when the covenant community becomes a missional community.

As members of the covenant family we are in relationship with God and one another. We have a responsibility to invite others through the Gospel to enjoy the same covenant privileges as we enjoy. This is when the covenant community becomes a missional community.

The Islamic Antichrist

The Islamic Antichrist

The Insanity of Obedience

The Insanity of Obedience

Brimstone: The Art and Act of Holy Non-judgment

Brimstone: The Art and Act of Holy Non-judgment

Life on Mission: Joining the Everyday Mission of God

Life on Mission: Joining the Everyday Mission of God

Untamed: Reactivating a Missional Form of Discipleship

Untamed: Reactivating a Missional Form of Discipleship