by John Howard Yoder

Yoder wrote his book to illustrate the non-violent social ethic behind Jesus’ teachings. If we view Jesus mainly as the Lamb of God, who came solely to save his people from their sin, we will fail to understand that Jesus also came as the anointed and rightful King of Israel, the Messiah whose purpose was to introduce a new kingdom and way of life that will supplant and overthrow the kingdoms of this world. As Jesus told Pilate, his kingdom is not of this world, nor do its adherents use the tactics and weapons of this world. Nevertheless, Jesus and his kingdom posed and still pose a real threat to the existing order of things. For that reason, Jesus was nailed to a cross as in insurrectionist with “The King of the Jews” emblazoned on the sign above his head. In so doing the powers of the world system hoped to put an end to his kingly aspirations and the radical social change espoused by his teachings. They failed.

According to Josephus, Herod imprisoned John the Baptist out of a fear that he might foment an insurrection. The mood of the people was restless, and their hope was that a Messiah would soon appear who would lead a successful revolt to throw off the oppressive power of Rome. John announced the coming of such a leader, the long awaited Messiah, the promised son of David. John identified Jesus as the promised one, the Messiah. Later Jesus corroborated to his disciples that he indeed was God’s anointed one. But Jesus did not come to fulfill his followers expectations. Rather, he came to fulfill his Father’s will, which was first to die as God’s Lamb to atone for sins and reconcile people back to God. After his resurrection he promised to come again one day to finally and fully install God’s glorious kingdom on earth. In the meantime, his followers are to preach the good news of his kingship and kingdom, as it spreads and permeates the world system as leaven permeates a lump of dough.

Jesus’ temptations in the wilderness prior to his public ministry were all related to his kingship and how he would gain authority and power. Would he use the methods of the evil powers of the world system (and Satan) or employ the hidden, counter-intuitive, and mysterious way of the cross? Would he “buy” his support by feeding the multitudes with bread? Would he bow down to the idolatrous pull of power and glory? Would he save himself from being put to death as a blasphemer by being thrown from the parapet of the temple? Jesus repulsed each of these temptations, remaining true to his Father’s will. Only one temptation assaulted Jesus throughout his ministry – to avoid the cross. It came from the mouth of Peter. It confronted him in the garden of Gethsemane, and it made one final attempt to lure him away from the full acceptance of his path to glory as he hung on the cross. His tormentors challenged him to save himself if he really were the Messiah.

Jesus would have been justified in calling twelve legions of angels to rescue him and usher him into his rightful place upon the throne of Israel, but that was not God’s way. The way of the cross demanded that he shun any attempt to use the methods and means that the ungodly powers and principalities that run the “cosmos” employ. Jesus refused to use armed force and violence to defeat those who had the most powerful armed forces in the world and used them to intimidate and punish any who might resist. His kingdom would come another way by another dynamic altogether. That is why he told Pilate:

“My kingdom is not of this world. If my kingdom were of this world, my servants would have been fighting, that I might not be delivered over to the Jews. But my kingdom is not from the world.” John 18:36 (ESV)

The principalities and powers use violence and intimidation to conquer, oppress, rule, and enslave. The dominant myth in our world, which almost everyone has adopted unquestioningly, is that it the only possible way to survive and thrive in this world is by operating according to the rules imposed on us by the spiritual world system constructed by satanic world powers. Walter Wink, in his book entitled The Powers that Be, calls this the myth of redemptive violence.

Jesus was born in Israel at the zenith of Rome’s world domination and military power into a nation which was under its thumb. He arrived as the long awaited Messiah, who, it was thought, would lead the Jews in an armed revolt against her oppressors and restore her former glory as a world power. These expectations were only partly right. Jesus actually came as the LORD of LORDS, the ruler of the universe, to whom every knee would one day bow; however, he came to install a radically different kingdom that would not be ruled or influenced by the principalities and powers of the satanic world system. For this to happen, he had to first defeat those powers through the mysterious work of the cross.

Jesus and the Jubilee

Yoder shows that Jesus’ teachings were profoundly influenced by his understanding of the meaning of the Jubilee, which many believe occurred in AD 26. The four main prescriptions of the Jubilee were:

- Leaving the soil fallow,

- Remitting debts,

- Liberating slaves, and

- Returning family property to each individual.

The second and third points are central to Jesus’ theology and teaching. (p.61) The Lord’s Prayer is a jubilatory prayer, the theme of which is

“the time has come for the faithful people to abolish all the debts which bind the poor ones of Israel, for your debts toward God are also wiped away. ” (p.62)

The Galilean peasant had been reduced to slavery because of the horrendous burden of taxation imposed by Herod the Great. This situation was further exacerbated by absentee landowners who hired intermediaries to manage their properties. These “stewards” were often crooked, cheating both the landowners and the tenant farmers. Jesus came to liberate the poor from oppressive debts, the prisoners from prison, and the brokenhearted from their pain and hopelessness. In so doing, Jesus attacked another bastion of the principalities and powers – the use and abuse of wealth to dominate and enslave. Instead Jesus advocated radical generosity and the renouncing of every form of worship of Mammon.

His kingdom and his followers would operate on another plane altogether, which called for a new mentality (metanoia – change of thinking, repentance). His kingdom would be known for its unselfishness and sharing. The jubilee also meant that slaves would be set free, which extended to those held in bondage to sin. The Jewish authorities took special offense at his claiming to have authority from God to forgive. In the Lord’s prayer, Jesus shows that debt is paradigmatic of evil, which is especially interesting in light of the United States hopeless servitude to Mammon and the resulting staggering indebtedness that has engulfed us. Jesus came to liberate slaves, debtors, and sinners and to install a new social ethic in his new kingdom in which slaves would be set free, debtors released, and sinners forgiven.

The Cross

The demonic cosmic world powers were enraged at the presence of this new king and his new kingdom ethic that threatened their rule. The Romans operated fully under this evil cosmic system and unquestioningly attempted to stamp out any type of insurrection that posed a threat to their domination. The Jewish leaders were complicit and sought to maintain their place, privilege, and power within the Roman hierarchy. Anyone (Jesus) who posed a threat to that position would be dealt with using brutal force.

As opposition to Jesus grew, he began to teach his disciples that he must die an insurrectionist’s death on the cross. He called his followers to commit themselves to being a

“community of voluntary commitment, willing for the sake of its calling to take upon itself the hostility of a given society… a disciple is to share in that style of life of which the cross is the culmination… [a] community of disciples [with] sociological traits most characteristic of those who set about to change society: a visible structured fellowship, a sober decision guaranteeing that the costs of commitment to the fellowship have been consciously accepted, and a clearly defined life-style distinct from that of the crowd.” (pp. 37-39)

When Jesus entered Jerusalem in Luke 19:36-46, he did so as the Messianic son of David. His “cleansing of the temple” illustrated his authority in the spiritual realm. With the people behind him, his next logical step would have been to gather an army and assault the Roman garrison, but he would not. Instead Jesus retreated to Gethsemane to await his fate. His enemies understood that they must put him to death because his claims to be the Messiah were clearly understood and could only lead to trouble for the powers that currently ruled.

Scot McKnight’s book, The King Jesus Gospel, is very helpful at this point. McKnight clearly demonstrates that the gospel is much more than proclaiming that Jesus is the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world. Rather, it must be clearly declared that Jesus is also the LORD of LORDS who is coming again to take the throne of David, which is his by divine right. Jesus destiny will be to usher in the full expression of his Father’s jubilee-oriented kingdom. It is vital to understand that Jesus’ messianic claims were political in nature, which the Romans, Herod, the Jewish authorities, and Jesus’ own disciples clearly understood. If we fail to understand this, our gospel message will be diminished. We must proclaim Jesus, the Messianic King of Israel, not just forgiveness of sins!

The cross stands for the person who loves his enemies, whose righteousness is greater than that of the Pharisees, who being rich became poor, who gives his robe to those who took his cloak, who prays for those who evilly use him. The cross is not a detour or a hurdle on the way to the kingdom, nor is it even the way to the kingdom; it is the kingdom come… Jesus was, in his divinely mandated…prophethood, priesthood, and kingship, the bearer of a new possibility of human, social, and therefore political relationships. His baptism is the inauguration and his cross is the culmination of that new regime in which his disciples are called to share…[We cannot] avoid his call to an ethic marked by the cross, a cross identified as the punishment of a man who threatens society by creating a new kind of community leading a radically new kind of life. (pp. 51-53)

Such an understanding of the cross is central to Yoder’s book. He writes:

The believer’s cross is, like that of Jesus, the price of social nonconformity. It is not like sickness or catastrophe, an inexplicable, unpredictable suffering; it is the end of a path freely chosen after counting the cost… it is a normative statement about the relation of our social obedience to the messianity of Jesus. Representing as he did the divine order now at hand, accessible; renouncing as he did the legitimate use of violence and the accrediting of the existing authorities, renouncing as well the ritual purity of noninvolvement, his people will encounter in ways analogous to his own the hostility of the old order. (p.96)…

Between the absolute agape which lets itself be crucified and effectiveness (which it is assumed will usually need to be violent), the resurrection forbids us to choose, for in the light of the resurrection crucified agape is not folly (as it seems to the Hellenizers to be) and weakness (as the Judaizers believe) but the wisdom and power of God. (1 Cor. 1:22-25) (p. 109)

Principalities and Powers

Yoder’s chapter entitled Christ and Power gives the reader insight into the nature of spiritual warfare and the church’s mission to manifest the wisdom of God in the face of hostile world rulers. From the beginning of creation, “powers” have had their place in God’s order. When Paul wrote that all things “subsist” in Christ (Colossians 1:17), the Greek word used was the same root as our modern word “system.” In Christ, everything systematizes and holds together. (pp. 140-141)

Rather than being benevolent, as they were at the time of creation, they now seek to

- Separate us from God’s love (Romans 8:38),

- Rule over those who are far from God (Ephesians 2:2),

- Hold us in servitude to their rules (Colossians 2:20), and

- Hold us under their tutelage. (Galatians 4:3)

These structures or powers which were created to serve us, have become our masters and guardians. (p. 141) Yoder points out that tyrannical domination by the powers is nevertheless better than chaos. God orders the powers under his sovereignty. (Romans 13:1) We cannot live without them, because that would be chaos, and we cannot live with them, for they have absolutized themselves and demand from the individual and society unconditional loyalty, bringing us into slavery and harm. (p. 143)

Yoder writes:

If then God is going to save his creatures in their humanity, the Powers cannot simply be destroyed or set aside or ignored. Their sovereignty must be broken. This is what Jesus did concretely and historically, by living a genuinely free and human existence. This life brought him, as any genuinely human existence will bring anyone, to the cross. In his death the Powers – in this case the most worthy, weighty representatives of Jewish religion and Roman politics – acted in collusion. Like everyone, he too was subject (but in his case quite willingly) to these powers. He accepted his own status of submission. But morally he broke their rules by refusing to support them in their self-glorification; and that is why they killed him… Here we have for the first time to do with someone who is not the slave of any power, of any law or custom, community or institution, value or theory. Not even to save his own life will he let himself be made a slave to these Powers… He disarmed the principalities and powers and made a public example of them, triumphing over them [in the cross]. Colossians 2:15. (p. 145)

The Work of the Church and the Powers

Paul wrote that the church is the vehicle for “the manifold wisdom of God” to “be made known to the rulers and authorities in the heavenly places.” [Ephesians 3:10 (ESV)]

The very existence of the church, in which Gentiles and Jews, who heretofore walked according to the stoichea [elements of reality] of the world, live together in Christ’s fellowship, is itself a proclamation, a sign, a token to the Powers that their unbroken dominion has come to an end… All resistance and every attack against the gods of this age will be unfruitful, unless the church… demonstrates in its own life and fellowship how believers can live freed from the Powers. (p. 148)

This is a monumental insight! The church must model freedom from Mammon, nationalism, racism, and every other dividing, enslaving Power. Seeing this truth unmasks how the modern “conservative” church has embraced the Power of revolutionary politics in order to justify the use of violence to resist a tyrannical government, something Jesus never taught nor modeled. It also takes the mask off of the “health and wealth gospel,” which has been co-opted by Mammon. It is vital that the church breakthrough in all these areas as an act of obedience to Christ and defiance against the rule of the Powers.

It is thus a fundamental error to conceive of the position of the church in the New Testament in the face of social issues as a “withdrawal,” or to see this position as motivated by weakness, because of Christians’ numerical insignificance or low social class, or by the fear of persecution, or by scrupulous concern to remain uncontaminated by the world.

What can be called the “otherness of the church” is an attitude rooted in strength and not in weakness. It consists of being a herald of liberation and not a community of slaves. It is not a detour or a waiting period, looking forward to better days which one hopes might come a few centuries later; it was rather a victory when the church rejected the temptations of the Zealot and the Maccabean patriotism and Herodian collaboration. The church accepted the gift of being the “new humanity” created by the cross and not by the sword. (pp. 147-148)

That Christ is Lord, a proclamation to which only individuals can respond, is nonetheless a social, political, structural fact, which constitutes a challenge to the Powers… The Powers have been defeated by… the sovereign presence, within the structures of creaturely orderliness, of Jesus the kingly claimant and of the church which is itself a structure and a power in society. The historicity of Jesus retains , in the working of the church as it encounters the other power and value structures of its history, the same kind of relevance that the man Jesus had for those whom he served until they killed him.(pp. 156-158)

Revolutionary Subordination

The chapter with the above title discusses what theologians call the Haustafeln, the early Christian ethical thinking. Yoder shows that it was not merely an adoption of an already existing teaching, but was in fact quite revolutionary. An example of this teaching can be found in the following passages – Colossians 3:18-4:1, Ephesians 5:21-6:9, and 1 Peter 2:13-3:7.

The subordinate person in the social order is addressed as a moral agent. She [or he] is called upon to take responsibility for the acceptance of her position in society as meaningful before God… Here we have a faith that assigns personal moral responsibility to those who had no legal or moral status in their culture, and makes of them decision makers…

In the Haustafeln,… the center of the imperative is the call to willing subordination to one’s partner… Subordination means the acceptance of an order, as it exists, but with the new meaning given to it by the fact that one’s acceptance of it is willing and meaningfully motivated… [which gives people a] new kind of dignity and responsibility… They are all related specifically to the person of Christ and the work of the church. (pp. 171-176)

Yoder shows that the teaching of the Haustafeln was necessary because the Gospel so liberated those who had previously had no status or standing that they had to be shown how to accept a subordinate role in society where necessary.

After having stated the call to subordination as addressed to those who are subordinate already, the Haustafeln then go on to turn the relationship around and repeat the demand, calling the dominant partner in the relationship to a kind of subordination in turn…That the call to subordination is reciprocal is once again a revolutionary trait. (p. 177)

To accept subordination within the framework of things as they are is not to grant the inferiority in moral or personal value of the subordinate party. In fact the opposite is true; the ability to call upon the subordinate party to accept that subordination freely is, as it was in the Haustafeln, a sign that this party has already been ascribed a worth that is fundamentally different from what any other society would have accorded. (p. 181)

The liberation of the Christian from “the way things are,” which has been brought about by the gospel of Christ, who freely took upon himself the bondages of history in our place, is so thorough and novel as to make evident to the believer that the givenness of our subjection to the enslaving or alienating powers of this world is broken…

But precisely because of Christ we shall not impose that shift violently upon the social order beyond the confines of the church… We may have reason to hope that the loving willingness of our subordination will itself have a missionary impact… The voluntary subjection of the church is understood as a witness to the world. (p. 185)

Relating to Secular Government

Yoder next addresses how revolutionary subordination affects our relationship with secular government. This is perhaps one of the most important chapters in the book, considering how conservative Christians have bonded with the American revolutionary ethic of armed resistance to tyranny. Yoder writes:

There is a very strong strand of Gospel teaching which sees secular government as the province of the sovereignty of Satan. This position is perhaps most typically expressed by the temptation story, in which Jesus did not challenge the claim of Satan to be able to dispose of the rule of all the nations… Romans 13 was written about pagan government. It constitutes at best acquiescence in that government’s dominion, not the accrediting of a given state by God or the installation of a particular sovereign by providential disposition… There is a strong strand of apostolic thought that sees the state within the framework of the victory of Christ over the principalities and powers… In the book of Revelation, most pointedly in Chapter 13, we find an image of government largely comparable to the one we referred to in the earliest portions of the Gospels. The “Powers” are seen as persecuting the true believers… (pp. 194-196)

Yoder makes the case that Romans 13:1 means that:

God is not said to create or institute or ordain the powers that be, but only to order them, to put them in order, sovereignly to tell them where they belong, what is there place… there has been hierarchy, authority, and power since human society existed. Its exercise has involved domination, disrespect for human dignity, and real or potential violence ever since sin existed. Nor is it that by ordering this realm God specifically, morally approves of what government does… God orders them, brings them into line, providentially and permissively lines them up with divine purposes. (pp. 201-202)

The Christian who accepts subjection to government retains moral independence and judgment. The authority of government is not self-justifying. Whatever government exists is ordered by God; but the text does not say that whatever the government does or asks of its citizens is good. (p. 205)

The willingness to suffer… is itself a participation in the character of God’s victorious patience with the rebellious powers of creation. We subject ourselves to government because it was in so doing that Jesus revealed and achieved God’s victory. (p. 209)

“The lamb that was slain is worthy to receive power!” John is here saying…that the cross and not the sword, suffering and not brute power determines the meaning of history. The key to the obedience of God’s people is not their effectiveness but their patience…The triumph of the right, although it is assured, is sure because of the power of the resurrection and not because of any calculation of causes and effects, nor because of the inherently greater strength of the good guys… but one of cross and resurrection. (p. 232)

The name “Christ,” that is, the one anointed to rule, …. was inseparable from the political concerns then related most intimately to fulfilling the hopes of his people in their oppression… The choice that he made in rejecting the crown and accepting the cross was the commitment to such a degree of faithfulness to the character of divine love that he was willing for its sake to sacrifice “effectiveness.”… What Jesus renounced was thus not simply the metaphysical status of sonship but rather the untrammelled sovereign exercise of power in the affairs of that humanity amid which he came to dwell…

But the judgment of God upon this renunciation and acceptance of defeat is the declaration that this is victory… affirming that the dominion of God over history has made use of the apparent historical failure of Jesus as a mover of human events. (pp. 234-236)

This gospel concept of the cross of the Christian does not mean that suffering is thought of as in itself redemptive or that martyrdom is a value to be sought after. Nor does it refer uniquely to being persecuted for “religious” reasons by an outspokenly pagan government. What Jesus refers to in his call to cross-bearing is rather the seeming defeat of that strategy of obedience which is no strategy, the inevitable suffering of those whose only goal is to be faithful to that love which puts one at the mercy of one’s neighbor, which abandons claims to justice for oneself and for one’s own in an overriding concern for the reconciling of the adversary and the estranged… It is rather our readiness to renounce our legitimate ends whenever they cannot be attained by legitimate means itself constitutes our participation in the triumphant suffering of the Lamb. (pp. 236-237)

There is a widespread recognition that Western society is moving toward the collapse of the mentality that has been identified with Christendom.

Christians must recognize that they are not only a minority on the globe but also at home in the midst of followers of non-Christian and post-Christian faiths. Perhaps this will prepare us to see how inappropriate and preposterous was the prevailing assumption, from the time of Constantine until yesterday, that the fundamental responsibility of the church for society is to manage it…A church once freed from compulsiveness and from the urge to manage the world might then find ways and words to suggest as well to those outside its bounds the invitation to a servant stance in society. (pp. 240-241)

Conclusion

I urge you to read both The King Jesus Gospel by Scot McKnight and Yoder’s work. Understanding the truths found in these two books will enhance your concept of the gospel and the cross. They will give you greater clarity concerning what it means to be part of the church’s call to manifest God’s wisdom to the principalities and the powers. You will see how important it is for the church to be the new humanity that lives out the teachings of Jesus in a world enslaved by sin and the world system of powers and principalities. You will find yourself being stirred in the core of your being with an excitement that comes from serving and proclaiming the King of Kings and his world altering kingdom Gospel. May the church arise from is slumber and malaise to become the world changing force she was designed to be!

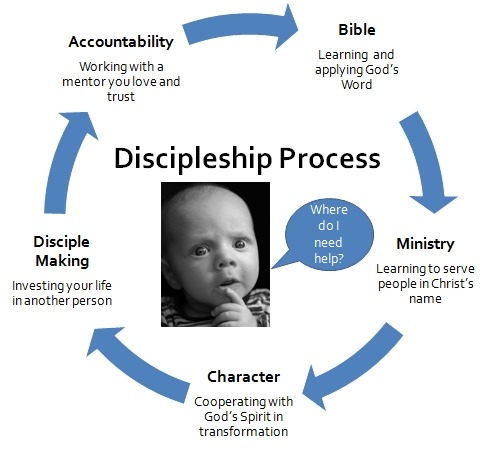

Bill shares that most churches do a pretty good job at focusing on growth in knowledge of the Bible, learning ministry skills, and focusing on inner character transformation. Where we break down is usually in the area of being personally accountable to a mentor and in making a commitment to invest in at least one other person at any given time. I would add that unless sharing the Gospel with those who do not yet know Christ is added to the cycle, we will miss a fundamental aspect of disciple making.

Bill shares that most churches do a pretty good job at focusing on growth in knowledge of the Bible, learning ministry skills, and focusing on inner character transformation. Where we break down is usually in the area of being personally accountable to a mentor and in making a commitment to invest in at least one other person at any given time. I would add that unless sharing the Gospel with those who do not yet know Christ is added to the cycle, we will miss a fundamental aspect of disciple making.